The concept of continual improvement, influenced significantly by visionaries such as Sir Edward Deming in the 1950s, laid the groundwork for a structured approach to quality management, exemplified by the continual improvement (PDCA) cycle. Originally rooted in the context of factory-type work, where manual labor synchronized with machines, the focus was on optimizing workflows, eliminating waste, and ensuring consistency in outputs—a paradigm where metrics were easily collectible and amenable to statistical analysis. Over time, continual improvement practices transcended industrial boundaries, extending into the service industry and general management. Even ISO norms advocate for continual improvement, urging practitioners to continuously refine practices outlined in a specific ISO norm.

Despite the shift from an industrial era to a knowledge-based economy, with a predominant workforce engaged in intellectual pursuits, continual improvement remains a revered best practice. However, the question arises: is the application of continual improvement universally suitable? Should we persistently enhance activities that may have become obsolete or less significant? Is it plausible to continually refine one-time decisions or activities influenced by externalities and unknown variables? The answer, unequivocally, is no. Continual improvement proves to be domain-dependent, finding its forte in highly regular and consistent activities.

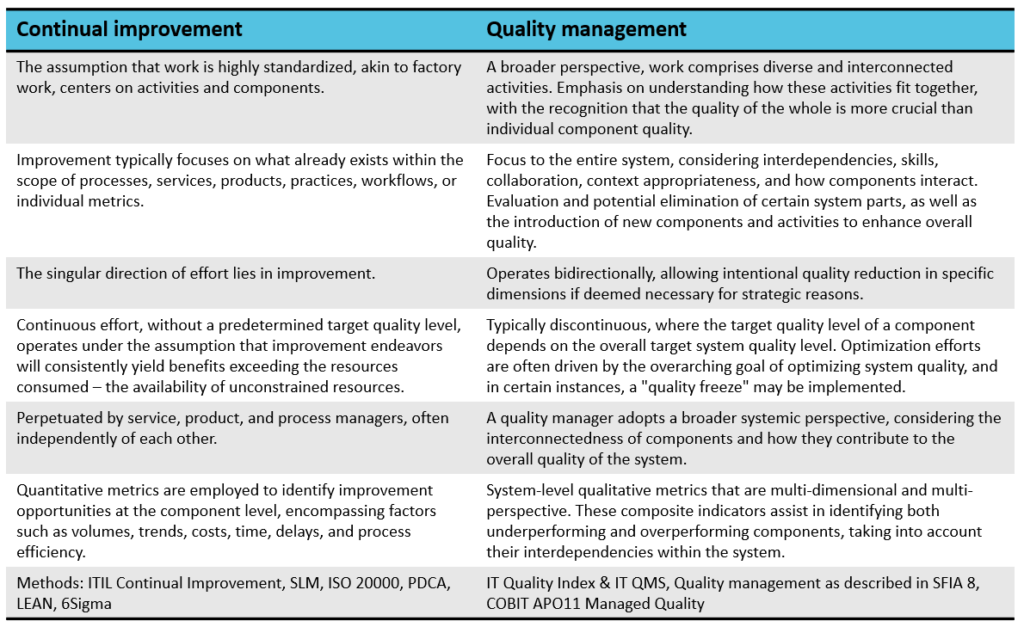

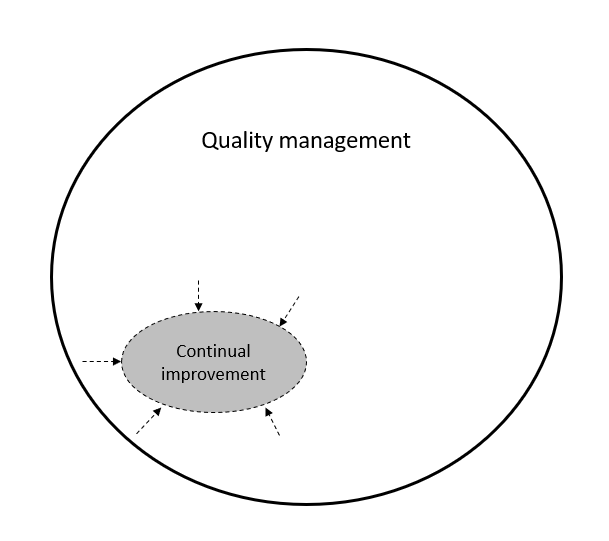

For a majority of work activities, alternative approaches may yield superior results, such as continual learning and adaptation or quality management in its broader meaning. Here are key considerations:

- ‘Good Enough’ Approach: Embracing a “good enough” mentality is not only acceptable but often preferable for many work activities.

- Strategic Decision-Making: Identifying and halting activities of low importance, automating, or delegating them can be more effective than continuous improvement efforts.

- Holistic Metrics Evaluation: Rather than optimizing a single metric in isolation, it’s crucial to consider a comprehensive array of metrics or composite indicators representing multidimensional perspective. For instance, incessantly enhancing customer experience (CX) may be counterproductive if the underlying economic dynamics with a particular customer are unfavorable.

The evolution toward knowledge work necessitates a critical reevaluation of where and why continual improvement practices should be applied. Adapting to the intricacies of contemporary work environments may entail embracing approaches like continual learning and adaptation, recognizing that not all activities warrant the relentless pursuit of improvement.